Personal Memoir – Allen Markle

I should have been in bed and asleep, but once Herb had come to our house last evening, I had been too excited. My uncle George was away at Tanamacoon with Grandma and Gramps. That left me without a close playmate. At least ‘til they came home after the camp closed and we had to go back to school. They went every summer that I could remember; Grandma to cook and clean and Gramps working as a handyman. Though telling stories and taking people out fishing were his long suit. So, when Herb had asked Dad to tend the cattle while he and his family took a long weekend at their cottage on Tasso Lake, Dad had said yes. He had also assured me that I could go with him in the morning. As long as I was up and ready. Excitement had driven sleep from me.

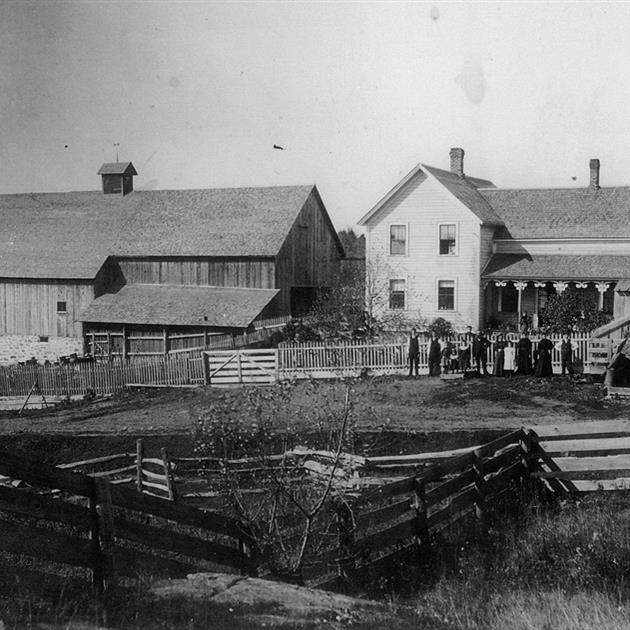

Great Uncle John and Rose Carter had the farm across the road from our house, the big square frame building sitting well back from Brunel Road as it still is today. Always painted white and with a driving shed just up the hill a bit, and on the other side of the laneway. The barn sat at the top of the rise with the dome of the silo showing over the roof. A huge hill reared up beside it.

Carters’ barn being across the road was not a place I went unaccompanied. Dad or Gramps had to be going or sometimes Uncle John would come and fetch me to help with some little thing. Mostly, I think he just wanted the company. I loved spending time there, partly because of the barn and partly because of the stories I would hear. Those old folk could really tell you stuff. John and Rose had two sons, Herb and Len plus two daughters, Elsie, a nurse, and Mary who had married Jack Laycock, a teacher in Huntsville.

I loved that barn; any old barn really, and even today I love the sight of the big old structures. Sadness creeps in when one is poorly maintained or neglected. In the early days, with oxen, cattle, horses, chickens and pigs inside, winter didn’t cause destruction as it can today. Once there isn’t any body heat to keep frost from creeping in, the old foundations begin to crack and crumble.

Herb and Uncle John worked the farm together, their animals wandering the fields and bush on the west side of Brunel Road. Sometimes they grazed up to the fence directly across from our house. Casually fertilizing the hillside and in my mind at least, making the flowers bloom. The dicentera or Dutch-mans’ Breeches were especially appreciative, growing and blooming in circles, much the size and shape as the cattle had left the compost. In spring, the flowers covered the ground beneath the maples. Hepatica, spring beauties, trillium, trout lilies and violets were all there for us to pick and give to Mom.

I was up with Dad that morning, eager to head across the road and up the lane to the big barn. Dad swung the door open and the heat and odour swept out and over us. The smell of manure and hay was in the forefront but there were traces of molasses, ammonia, milk, corn and turnip all mingling faintly in the background. Five A.M. didn’t seem early to the cattle who stood in their stalls slowly chewing their cuds and casting big baleful looks our way as we came in. Each animal stood in its own place; head captured in its’ own upright, metal collar.

Dad flipped on the light switch and started the compressor that ran the milking machine. There was a time when I had come here that the men had done some milking by hand, but not today. Dad was doing this favour before he went to work, so to him, as he would say, “time was wasting”. I wasn’t involved in the milking process, just there to explore that big old building. To run and fetch what I was asked, but mostly to enjoy the steady plunk and hiss of the machinery filling the space around me.

Stalls ran the full length of the barn with only a narrow walkway through along the right wall giving access to the manger side of them. The walkway led to an array of small pens that always stood empty. I was told that when Carters had raised ‘vealers’, that was where they had been kept.

There was also a big chopping machine with a funnel shaped bin on top. Turnips and corn could be shoveled in when the unit was running, dropping down onto the whirling blades. The chopped material was carried up and away on a conveyor belt, through a door in the barn wall and dumped into the silo. I can remember one spring when a liquid had seeped from the silo. It had puddled at the base and the cattle had lapped it up. The silage had fermented a bit and the cows became boisterous; the milk was ruined for a few days.

Uncle John never encouraged me to be around when they were chopping silage, telling me that the machinery was too dangerous for a little boy to be near. He was a kindly old man, smiled a lot, with one eye totally milky white with cataracts. But he meant what he said. I could go to the field when they were harvesting, but had to stay on the tractor path and well away from the barn. The field was where Maple Heights is today, the corn and turnips stretched back to and across the creek, then along behind the Vince and Slatter properties.

When I was older, I discovered that the ‘horse-tooth’ corn as my father had referred to it, was a type of ‘dent’ corn. Misapplying some French, I had decided that ‘dent’ in this case meant tooth. In fact, it meant that as this type of corn dries, each kernel develops a dent in the top. This is not the sweet corn that we buy for a corn-roast but is grown as feed for animals. Once processed it can feed people.

The barrier of Brunel Road stretched between me and the Carter property and visits there were not as frequent as I would have liked. There could be serious repercussions for being on the road although one could ask permission, have it granted and scoot across. But sometimes it was just too much of a hassle to go through the process so the urge would pass …but not always.

The need for access to a barn was alleviated by the fact that only my grandparents house stood between me and Uncle Dick Bucks’ barn. There was no road to cross. It took seconds to scoot between my grandparents’ house and the ice-house. Past the garden, around the corner of the barn and I was home-free.

Standing tip-toe on the big flat rock that was the step up into the barn and brandishing a long stick brought just for the purpose, success was close. Stretch up and enough to poke the hook out of the eye. The big door would swing open. Propping the door open ensured that it wouldn’t slam shut, alert Aunt Aggie or Uncle Dick. And get me caught. I wasn’t to be in the barn alone, but it always drew me like a magnet. I loved the smells.

Dick Buck wasn’t a really that close relative, but having married Agatha Slatter, my grandmas’ cousin, we always called him Uncle. He was a big, thick chested man with a full, white mustache, white hair peeking out from under a short-brimmed straw hat and usually in white shirt with arm cuffs and coveralls. It was said that he was quite a lady’s man and I always remember him being a polite but commanding presence.

He had purchased the property from Silas Jacobs on the 12th of November 1914, shortly after the death of Mr. Jacobs son Leslie, the previous March. Mr. Jacobs and his son had operated the mill at the Locks for several years. Undoubtedly, the timbers and lumber in the house and barn had been cut at that water-powered mill.

Sometimes Uncle Dick would get me to straighten nails on the big flat rock that served as the step I mentioned. There was a big horse-pail that he kept full of bent nails. Sometimes when he was in the garden, he would sit the pail out, give me a hammer and I would make them straight and useable again. Because you couldn’t afford to waste anything. Everyone could still vividly recall the war years. When nails and metal goods were rationed and in short supply. Often, a couple of cents would reward a job well done.

But not everything about the barn was pleasant, because just inside the door was where my dog Jack had lay suffering on the old horse-blanket that hung on the wall beside the grain barrel.

I had been told to not throw the ball over the bank toward the road. Jack loved to chase the ball and over the bank was where I could get it to go the furthest. The dog had plunged happily after the ball and the man in the car had no time to stop. He had been apologetic, trying to console me and explain what had happened to my mother. Uncle Dick had come with his wheel barrow and the man had helped him lift the whimpering Jack from the road, then get him to the blanket in the barn. They had said something about his back but I just knew my dog was hurt and I was the cause.

Once Dad was home, we took the lantern and went to the barn. The lantern hissed softly on the floor and I had sat in the halo of light, stroking the dog’s head as Uncle Dick and Dad had talked. Then they sent me home and I knew Jack was gone.

But still it drew me in….. that barn. The big flat rock step and the smell of molasses and hay. On the window ledge, coated in dust, were several porcelain ‘eggs’ that I liked to polish and rearrange and that would be put in the chickens’ nests to encourage the hens to lay eggs. There was a faint smell of horses and the odor of leather and salt in the collars and oil that had been rubbed into the pieces of harness that hung on the wall. I don’t remember there being horses in the barn very often but one time is still vivid in my memory.

Grampa and Dad had brought a team home for whatever reason and it had amazed me that those big bodies could ever go through that door. And when gramps had watered them with the big horse pails, it fascinated me, watching them drink; how the big muzzle would stretch down to the water. To see the vortices they created along either side of the pail when sucking up the liquid.

Grampa had led each horse up onto the step and through the door. Their shoes cracked on the stone step and thumped the threshold beam as they stepped inside. The barn was not large and the stalls barely contained those animals, but they settled, content with a manger full of fresh hay. Grampa put some oats in the chop box for the stallion and I made a fuss about putting the oats in the box for the mare. He put a measure of grain in a large tin can and gave it to me.

“Bang the can on the chop box after you dump the oats in mind you. She wants all of them.”

I went behind the horses with the can and had second thoughts about going between that big animal and the stall wall. There seemed to be too little space. But with a good shot of courage, in I plunged, really aware of how close she was and how enormous. I could just reach the top of the box to dump the grain and apparently my effort at banging the pail on the wood was not convincing enough for her.

When I began to move back along the wall, she shifted that big belly sideways and pinned my head to the side of the barn. It all happened so quick. She just pinned me, not hard, but it caused me to yelp and drop the can, which clunked loudly as it banged off the wall and hit the floor. That convinced her the pail was empty and all the grain was in her chop-box. As easily as she had pinned me, she let me go.

Grampa chuckled, “They love the oats. It’s like candy to them. And it’s where they get their energy when they have to work.”

Above one of the stalls, tucked between the loft joists were a pair of skis that Dad said had been used at the Huntsville ski jump. They were hand made of beech; long and broad and I always wanted to try them. Uncle Dick said they had been up there so long they would likely shatter if you were too rough with them. The top of the ski where your foot rested was concave and there was a broad leather strap that you fit your toe under. Then a loop of lamp wick was pulled under your toe, crossed over the top of your foot and then tied behind your ankle. Lamp wick was the harness of choice apparently and I know I even used it on snow-shoes.

The last time I remember seeing those skis the toe had no bend. The wood had remembered it had been straight before the curve had been steamed into it. I can remember a pattern carved in the toe of each ski. It reminded me of a palm tree. I suppose the ‘brand’ of the man who made them.

But there was only a faint smell of horses that particular day, maybe more in memory than on the air. The chickens had gabbled and chucked in their coop just through the door on the right. I turned left once inside and went along the wall to the ladder that led up to the loft. The boards used as rungs were worn smooth from use and I gripped each one firmly and headed up. The loft door was down, so it had to be pushed up and back out of the way. Once through the hole I could move away from the ladder and onto the loft floor.

There was little kept up here now. Mostly just old straw and chaff and dust. But the smell was intense. The air tickled drily in my nose and was clinging with heat. I sat with my back against the wall and watched the dust dancing in the sheets of light that cut away from the cracks between the boards. The light there and gone as the clouds drifted across the sun outside.

But my reveries were short lived as suddenly there was a solid thumping on the barn wall and Aunt Aggie was calling out.

“Allen. Are you in there? You know you shouldn’t be. Come out here now and get this door shut.”

And my time in the barn was over for now. But I think we both knew I would be back and that I would eventually twig to the fact that propping the door open only announced I was in the barn.

In 1953 Uncle Dick passed away; Aggie left and the farm was purchased by Elvin Tebby who brought a new family to our neighborhood. Elvin liked his garden, tapped the big maples in the yard for making syrup each spring and even raised some pigs the first few years that he lived there. My father and grandfather both got in on the butchering and cutting process in the fall. Mrs. Tebby made what adults called ‘head-cheese’ and although I was somewhat reticent about trying it, after helping scrape and glean every scrap of flesh from the carcass, I gave it a try. It was great on fresh bread with hot mustard and not very much different from the ‘pot-meat’ Gram and Grampa Hayes served when we visited them.

Mrs. Tebbys’ kitchen was on our list of favorite spots to hit in October when it was time for ‘trick or treat’, because she was another who gave out homemade! Imagine trying to do that today. But back then there were many who did homemade stuff and those treats were preferred by us. You would get candy apples, popcorn with nuts and raisins, dried fruit, home-made chocolates, fresh baked cookies, fruit and nut squares and other surprises. The one purchased thing you always got was molasses flavored chewy things that were individually wrapped in orange paper printed with witches and cats and moons. Never did like them.

Elvin cleaned away a lot of the brush on the property and one year he planted runner beans and sweet-peas around the west end of the barn. He enriched the soil with copious quantities of aged chicken manure. The results were spectacular, with the runner beans hooking into the cracks between the boards on the wall and climbing to the gable-end. I could pick Kentucky Wonder and Scarlett runner beans from the loft door! Adding colour to the whole were the sweet-peas. Bright splashes of pink, mauve and white mingling with the green leaves and the purple and scarlet flowers of the runner beans.

At the hunting camp one year, after doing renovations on his kitchen, Elvin told us of having found some papers in a box that listed expenses for building the house. He mentioned the owner recorded that the purchase of the land and materials, paying to have the house built and the construction of the barn had been done for under 600 dollars.

That barn left me with one last memory a few years after Tricia and I were married. Maybe around 1976. We had taken the boys and Donna our foster daughter to town for dinner. Just seated in the McDonalds’ restaurant on Main Street and about to order, our youngest boy became violently ill. I had been struggling with tonsillitis and now Aaron was sick. And then both Craig and Donna began to suffer. Tricia gathered us all, packed us into the car and headed for home.

I don’t remember her getting us into the house nor her putting me to bed. When tonsillitis struck me back then all I could do was go to bed, drink lots of fluids, pile on the blankets and tough it out. And suddenly I was awake, drenched with sweat. The room around me was flashing and flickering orange and red. I’m in hell I thought. Damn! I wrapped a blanket around myself and shuffled into the kitchen. Tricia was looking out the window, the room was flooded with quivering orange light and pulsed through with red flashing from the fire truck.

“Tebbys’ barn is on fire!” she said and we stood and watched for a while.

“I thought I was in Hell” I said.

“I was earlier” she replied. “You were a sick bunch. I could hardly get you into the house. And I never got any supper.”

There was no thought of me eating so I just shuffled back to bed.

The next day I went to look and the old barn still stood there. Somewhat charred and surrounded by the tracks and scufflings of those who had fought to save it. My grandmother said she feared that the flames would leap to her house. Elvin replaced a few boards, inserted some reinforcing here and there and the barn went on. It still stands on the edge of Brunel Rd. A reminder of earlier days.

Today I can still visualize the inside of those old barns but the Buck barn in particular. I can feel the warm boards through my shirt as I lean back against the wall. I close my eyes and feel surrounded by the heat and the smells of the loft. When a cloud uncovers the sun, I can watch as sheets of light fire through the cracks between the boards, giving the dust a place to dance.